Flexographic Printer: Efficient Emissions

Comments Off on Flexographic Printer: Efficient Emissions The Challenge

The Challenge

Control of air emissions has become an important issue that flexible packaging converters must consider when changing or upgrading equipment. A producer of printed shrink films, bags and pouches for a diverse range of applications addressed its emissions in 1991 and 1996 by investing in two Anguil catalytic oxidizers to control the EPA-regulated air emissions generated in their various processes.

But when the company decided to purchase a new 10-color gearless press to increase capacity and capability years later, management knew they also needed to determine if an alternate technology would reduce their operational costs compared to their two catalytic oxidizers.

The Solution

Having supplied the original catalytic oxidizers, the customer contacted Anguil Environmental to analyze the most cost-effective and compliant way to replace the two aged systems. After an analysis, Anguil recommended replacement of the existing equipment with a single 25,000 Regenerative Thermal Oxidizer (RTO).

The Result

RTOs Replace Catalytic Oxidizers

Though the catalytic units were a logical choice at the time of purchase, technological advances in the ensuing years had caused the RTO to become a much more viable abatement strategy.

Now 15-20 years following the original catalytic oxidizer installations, the customer and Anguil’s objectives were to:

- Achieve destruction of 98 percent of the Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) in the press exhaust

- Fit the system into limited space

- Complete the tear-out and subsequent installation in just six days

The operation of the RTO is considerably different from the existing catalytic units. The oxidizer consists of two reinforced, insulated chambers filled with high temperature structured ceramic energy recovery media. The oxidizer utilizes a burner to maintain the oxidation temperature. Located beside the energy recovery chambers are diverter valves and air duct plenum passages, which allow the press exhaust to be diverted into and out of the oxidizer in either a clockwise or counterclockwise mode. The directional mode is controlled by a PLC, which changes the direction of airflow at regular intervals to optimize system efficiency.

The RTO in Action

The RTO in Action

In operation, solvent laden air (SLA) enters the oxidizer via an energy recovery chamber where the high temperature ceramic heat transfer media preheats the SLA prior to introduction into the oxidation chamber. As the SLA passes up through the bed, its temperature rapidly increases. After the chemical oxidation purification reaction occurs, the hot, clean, outgoing gas heats the exit energy recovery bed. In order to maintain optimum heat recovery efficiency, the SLA flow direction is switched at regular intervals by the automatic diverter valves on demand from the PLC control system. This periodic flow direction shift provided a high thermal efficiency to minimize customer operational cost.

With sufficient concentration of hydrocarbons in the process air stream, the heat energy content of the VOCs will result in self-sustained operation with no auxiliary fuel usage.

Features that are specific to the RTO include:

- High volumetric turn-down capability, enabling the control of multiple presses and the reduction of operating cost.

- Thermal energy recovery of 95 percent or higher, allowing self-sustaining operation with no auxiliary fuel usage at levels as low VOC exhaust concentrations..

- Customized thermal energy recovery media, providing low-pressure drop and low electrical cost.

Anguil’s vast experience, gained after supplying more than 2,000 successful systems around the world, provided the confidence necessary for this customer to choose Anguil as their continued VOC control supplier for three decades and counting. Anguil was able to modify its standard RTO design to fit into the space provided and to execute tear-out and new installation within a short timeline. The result was a system that exceeded the 98 percent destruction efficiency objective while lowering operating cost by more than 60 percent.

Converter Finds Affordable Compliance Solution

Comments Off on Converter Finds Affordable Compliance Solution The Challenge

The Challenge

It’s not just about increasing production for Fredman Bag’s president, Tim Fredman Jr., it’s also about being an environmentally conscious neighbor. A converter’s decision to expand their capacity is often made more complicated by a corresponding need to invest in air pollution control equipment. Recent expansions had Fredman Bag making major investments in their air pollution control equipment not only to meet EPA (Environment Protection Agency) regulations but also keep their reputation as a good neighbor.

The Solution

Fredman Bag, a Milwaukee-based flexible packaging converter purchased a new, eight-color, gearless CI-flexo press from Uteco Converting to adapt to their customer’s growing needs, enhancing their product offering and delivery capabilities. The gearless-press runs at faster speeds with a higher resolution, printing a superior-quality product and increasing production for Fredman Bag by nearly 40%.

The VOCs (Volatile Organic Compounds) and HAPs (Hazardous Air Pollutants) emitted by a printing press are not only harmful to the environment but also people who breathe them. Fredman Bag had been using an Anguil 6,000 SCFM (9,630 Nm3/hr) catalytic oxidizer as an effective means of air pollution control before their expansion but the increase in emissions and flow from the new press was beyond the capacity of the existing 10-year old oxidizer. After serious consideration, Fredman again turned to Anguil Environmental Systems, also a Milwaukee based firm, to address their pollution control needs.

The Result

The Result

Anguil’s application-specific engineering, stressing air volume reduction, energy-efficiency and improved emissions capture provides an affordable and flexible solution. Taking into consideration future growth, a 12,000 SCFM (19,260 Nm3/hr) Regenerative Thermal Oxidizer (RTO) was selected to ensure regulatory compliance. The Anguil RTO technology provides significant operating cost savings.

The Anguil two-chamber RTO heats exhaust air from the printing presses as it passes through beds of ceramic media located in an energy recovery chamber. The process air moves from the recovery chamber toward the combustion chamber, where the VOCs are oxidized, releasing energy into the second energy recovery chamber. A diverter valve switches the airflow direction so both energy recovery beds alternately store and release energy to minimize operating costs by reducing any auxiliary fuel requirement. This system is designed for heat recovery of over 95% and is self-sustaining, requiring little if any auxiliary fuel even with low VOC loadings. This energy-efficient recovery means the Anguil RTO offers lower operating costs over other emission treatment methods. As a result of Fredman’s decision to use the energy-efficient Anguil oxidizer, the company was eligible for Wisconsin Energy’s, Focus on Energy program. The incentives they received allowed them to go ahead with the project sooner than they had initially hoped.

Lost production was another concern for Tim Fredman, Jr. Air pollution control equipment doesn’t increase a manufacturer’s bottom dollar like other capital equipment does but it can often cost them significantly in downtime. Anguil took careful measures to assure that there were no disruptions in Fredman’s process. By utilizing existing ductwork, preparing accordingly and coordinating with the customer, Anguil was able to install the complete system in under three days. The oxidizer was delivered to Fredman Bag on a Thursday during a scheduled maintenance shutdown, installation was complete by Saturday and start-up was done that same day, saving the converter any lost production.

The Anguil system can be monitored and controlled 24/7 from remote locations for ease of troubleshooting and adjustments, eliminating unnecessary service calls. It has a high volumetric turndown capacity to minimize operating costs during process idle, downtime or on weekends. The Anguil oxidizer has been operating, maintenance free at 99% destruction rate efficiency since start-up. A trouble free air pollution control system allows Tim Fredman Jr. to concentrate on production and sales, knowing his company is in compliance.

RTOs Leave Nothing Hap-Penstance

Comments Off on RTOs Leave Nothing Hap-Penstance The Challenge

The Challenge

The United States EPA promulgated a ruling in 40 CFR, imposing strict new standards to reduce emissions of toxic air pollutants from the manufacture of pharmaceutical products, including prescription and over-the-counter drugs. The agency’s rule was intended to reduce emissions of a number of air toxins and hazardous air pollutants (HAPs), including methylene chloride, methanol, toluene and HCI. It was estimated at the time that the ruling would reduce air toxins annually by approximately 24,000 tons or 65 percent from contemporaneous levels. The affected pharmaceutical manufacturing processes included chemical synthesis (drawing a drug’s active ingredient) and chemical formulation (producing a drug in its final form).

The Solution

One of the approximately 100 facilities affected by the ruling was a pharmaceutical plant in upstate New York. Determined to stay below acceptable MACT levels, the company set out to establish compliance needs and subsequent direction by contracting with a consultant to formulate a compliance plan. The result was a specification package that required oxidation and caustic scrubber technologies.

The Result

The Result

Specifically, the design included a primary and backup system, each consisting of two 35,000 SCFM (56,175 Nm3/hr) regenerative thermal oxidizers (RTOs) and two 35,000 SCFM (56,175 Nm3/hr) caustic scrubber systems. The RTOs were to process the emissions, including methylene chloride, acetone, ethanol, isopropyl, alcohol, methanol and mineral spirits, and were designed to achieve over 99-percent destruction efficiency. The scrubbers were designed to process treated gases and achieve 99.5-percent reduction of the HCI derived from the oxidation process. After the design phase, the two technologies were selected in order to oxidize the VOC/HAP compounds, and to remove the resultant HCI emissions from the outlet of the oxidizer. Upon receipt of the specification package, the engineering staff at Anguil began to design the system within the boundaries of the specifications.

The specification package included the following requirements and parameters:

Process producing emissions – multiple (~60) sources including:

- Conservation vents

- Reactor vents

RTO materials of construction:

- Refractory selection: The RTO included the installation of high-purity ceramic fiber insulation, because of its resistance to HCI attack.

- Purification chamber outer skin: The purification chamber was constructed of 0.25 inch A36 Steel. It was internally blasted and coated with a vinyl ester corrosion-resistant coating. This coating resists any HCI (vapors or condensed acid) that could potentially reach the RTO shell behind the insulation. The coatings were pigmented so that the first coating was light gray and the second coat was dark gray. This allowed a visual inspection to identify that the coating was thoroughly applied during fabrication, and provides an easy means of checking for coating degradation after operation.

- Ceramic media support grid: The ceramic media support grid was constructed from Hastelloy C276 in order to support the ceramic media. This “cold face” has the potential too see condensed acid gas. Hastelloy C276 provides high strength and resists both chloride stress corrosion cracking and chloride pitting and crevice corrosion.

- Inlet plenum: The inlet plenum is the duct located underneath the RTO that connects to the three inlet butterfly diverter valves. The air flowing through this duct to the RTO contains VOCs and HAPs but does not contain acid gases. However, as a precaution against corrosion, this ductwork was constructed of AL-6XN, a corrosion resistant alloy.

- Outlet plenum: The outlet plenum is the duct located underneath the RTO that connects to the three outlet butterfly diverter valves. The air flowing through this duct to the RTO contains acid gases. This ductwork was constructed of Hastelloy C276.

- Bed/plenum/hopper: The plenum beneath each of the three ceramic media support grids was constructed of Hastelloy C276.

- Butterfly valves (bed inlet, outlet and purge): The three inlet diverter valves process air containing VOCs and HAPs. The three outlet diverter valves contain air containing acid gas. All sic valves were constructed of Hastelloy C276. The three purge valves were also constructed of Hastelloy C276.

- Transition to acid gas scrubber quench: The transition from the RTO outlet plenum to the acid gas scrubber quench contains acid gases. This ductwork was also constructed of Hastelloy C276.

Floor sweeps:

- Waste stream flow rate: 6,500-35,000 SCFM (10,432.5-56,175 Nm3/hr)

- Waste stream temperature: 50 to 100ºF

- VOC/HAP breakdown

The company possessed a long history treating halogenated compounds, including oxidation and acid gas scrubbing equipment. The two RTO and scrubber systems supplied here were actually installed after a smaller oxidizer and scrubber was operational within the same facility.

General Operational Description

Designing the oxidizer first, engineers specified that each RTO would process up to 35,000 SCFM (56,175 Nm3/hr) of VOC/HAP-laden air, providing 99.5% destruction efficiency.

Pharmaceutical Industry Pollution Control Solutions

The oxidizer consisted of three reinforced, insulated, steel chambers filled with high-temperature, structured ceramic energy recovery media. Each oxidizer would utilize two burners to maintain its oxidation temperature set-point, and provide even temperature distribution within the combustion chamber for maximum VOC/HAP destruction. Located below each of the energy recovery chambers would be inlet and outlet diverter valves and the associated air duct plenum passages. These would allow the process airflow to be diverted into and out of each of the heat recovery chambers. One duct would act as an inlet to the energy recovery chamber, the other as an outlet from the chambers to the acid gas scrubber. A third, smaller duct would direct heated purge air to each chamber. A purge valve for each chamber would control the flow of purge air into the chamber. The directional mode and purging would be controlled by a PLC program, which would change the direction of airflow at regular intervals to optimize system efficiency. The typical flow directions within the RTO would be adjusted every 90 seconds.

In operation, solvent-laden air (SLA) would enter the oxidizer via an energy recovery chamber, where the high-temperature ceramic heat transfer media would rapidly preheat it prior to its introduction into the oxidation chamber. After the chemical oxidation purification reaction occurs, the hot, clean, outgoing gas would heat the exit energy recovery chamber.

The SLA flow direction would be switched at regular intervals to maintain optimum heat recovery efficiency by the automatic diverter valves on demand from the PLC control system. After serving as an inlet, an energy recovery chamber would be purged for a cycle before serving as an outlet. This ensured that all air that entered a bed would be treated to the maximum extent possible. With sufficient concentration of hydrocarbons would self-sustain the oxidation process. The oxidizer can be operated in an off-line bake-out mode to allow the removal of organic buildup on the heat exchange media. The potential organic material consists of methylcellulose and lactose. In the bake-out mode, the RTO/scrubber trains are taken offline from the process. At a reduced airflow, the outlet temperature is allowed to rise before the flow direction is switched. This hot air vaporizes organic particulate collected on the cold face of the heat exchange media. The flow direction is switched and other cold faces are cleaned in succession.

Process Air Flow

Two 35,000 SCFM (56,175 Nm3/hr) systems were specified to provide redundancy while processing flows from 6,500 SCFM (10,432.5 Nm3/hr) to 35,000 SCFM (56,175 Nm3/hr). Each RTO/scrubber train would be functionally equivalent and operate in conjunction with or independent of each other. Each system could be returned down 6:1 (5,850 SCFM, 9,389.25 Nm3/hr). If the airflow to an individual RTO/scrubber was reduced below this level, a pressure control loop could open the fresh air damper to maintain the minimum system airflow. Butterfly isolation dampers were included at the inlet and outlet of each RTO/scrubber. The inlet isolation damper would be used to isolate an RTO/scrubber train during startup and shutdown. The outlet isolation damper would be activated when the RTO/scrubber was not in use. Butterfly isolation valves were included downstream of the scrubber; the manually operated valves would be used to isolate the RTO/scrubber train for service. A flanged blind was also included for installation downstream of the scrubber for isolation during service.

Fan Location

The RTO processes corrosive HCI vapors as the chlorinated hydrocarbons are oxidized. In a forced draft arrangement, the RTO is under positive pressure. In that configuration, the corrosive gases will tend to leak to atmosphere at the instrumentation (thermocouple) penetrations and the corrosive gases will condense at this interface corroding the outer shell. Therefore, an induced draft arrangement is typically preferred for chlorinated RTO applications. A fan was designed for the conditions at the scrubber outlet, including a radial blade fan wheel constructed of a corrosion resistant alloy, Hastelloy C276, and a carbon steel housing lined with rubber. This type of fan wheel was not as efficient as backward inclined or air foil designs, but it would not be as sensitive to aerosol droplets and offered a lower tip speed, reducing fan noise.

99.5% Destruction Efficiency Design

A residence time of two seconds at 1650°F was proposed to achieve an average destruction efficiency of 99.5 percent. Actual compliance test data demonstrated destruction efficiency in excess of 99.9 percent. In order to guarantee the high destruction efficiency that this project required, additional steps were taken to reduce the air not fully treated when the airflow changed direction. For the 99.5-percent destruction guarantee, the system was designed with three chambers. At any one time, one chamber would act as an inlet and one as an outlet, while the third was being purged. After serving as an inlet chamber, each chamber would be purged with heated clean air during the next cycle. The purge air would be heated to minimize the potential for HCI gas water vapor condensation and the resultant corrosion potential, even though high nickel and molybdenum alloys were used to resist corrosive effects. It would then become an outlet chamber during the next cycle. The three-chamber design also minimized any inlet/outlet bypass during valve cycling.

Acid Gas Scrubber

The acid gas scrubber was designed to process the maximum exhaust capacity of the RTO exhaust, including the purge air containing HCI vapor, providing 99.5-percent HCI removal. The horizontal quench was designed to cool the RTO exhaust to approximately 150°F. The re-circulation pumps provided water into the adiabatic quench through three separate spray headers. The air temperature was reduced to 150°F at the quench outlet. The water that was not evaporated flowed to the recycle sump. Approximately 50 percent of the HCI was scrubbed in the scrubber quench. The air left the horizontal quench and entered the bottom of a counter-current packed tower scrubber. Water and caustic solution was sprayed on the top of the tower. The remaining acid gases were absorbed by the solution as the air passed up the column. The air passed through a mist eliminator to remove entrained water before exiting the scrubber column. A sodium hydroxide solution was added to the re-circulating water to neutralize the adsorbed HCI and form sodium chloride (salt water), the sodium hydroxide addition rate controlled by pH analyzer. Salt water blow-down was controlled by a conductivity analyzer and by adding makeup water, causing sump overflow. The company worked closely with the customer and the consultant throughout the bid process, suggesting options and clarifying details on this major environmental project, and was also commissioned to install the systems. A tight site location necessitated the careful use of over-sized cranes so as to ensure no interference with or rupture of critical plant gas, air and nitrogen lines. Heavy rains throughout much of the process further complicated installation but ultimately the installation of all the equipment and the tie-in of the ductwork, electric and controls, without affecting process, were achieved. The result was a system, which surpassed the customer’s objective of 99.5 percent destruction efficiency and ensured compliance with the EPA’s pharmaceutical MACT.

ETO Sterilizer Abatement

Comments Off on ETO Sterilizer Abatement The Challenge

The Challenge

Product sterilization companies are generally required to utilize a pollution control device, often referred to as an abator, for treatment of exhaust gases from their aeration rooms, sterilization chambers and vessels. In the United States, they need to be in compliance with NESHAP (National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants) regulations that dictate a 99% destruction efficiency of EtO (Ethylene Oxide), or concentration levels below one part-per-million by volume.

One contract sterilization company was using a wet scrubbing system that was no longer a viable means of EtO removal. To further complicate the situation, their high production levels meant they could not afford a factory shutdown in excess of eighteen hours. This time limitation made the procurement of a pre-tested, pre-assembled pollution control system a necessity.

The Solution

After examining various technology alternatives and multiple suppliers, the sterilization company chose Anguil Environmental Systems to provide a catalytic oxidizer that would result in NESHAP compliance and minimal downtime.

A back-vent and peak shaver were also considered upstream of the oxidizer to prevent emission spikes from causing an upset condition. However, a detailed application analysis showed it was not necessary on this particular application.

The Result

Having experience with ethylene oxide emissions and sterilizer applications, Anguil recognized several unique challenges associated with this project. First, the catalytic oxidizer had to control both the high concentration, low air volume exhaust from the sterilization chamber’s vacuum pump, as well as the low concentration, high volume exhaust from the aeration room. The high concentration from the vacuum pumps of nearly 300,000 parts per million by volume caused a sharp temperature increase, and demanded that the catalyst have a large operational temperature window. At the same time, the catalyst needed a low operational temperature when treating the low concentration exhaust (10 parts per million by volume) from the aeration chamber.

To satisfy both these needs, Anguil, in conjunction with their catalyst supplier, performed extensive research and was able to supply a base metal type catalyst with an operational temperature of 275°F and an operational temperature window of over 500°F.

On some sterilizer installations, the highly concentrated chamber emissions present another set of challenges. Because they generally come in spikes when the chamber is evacuated, Anguil often recommends and installs a peak shaver or wet-scrubber upstream of the oxidizer as a safety precaution. Safety is always a priority on Anguil oxidizers. This buffer before the combustion device alleviates any concerns of property damage or personal injury.

The next challenge Anguil faced for this application was designing and building a system that not only met NESHAP regulations, but would also operate cost-efficiently. Due to stringent ethylene oxide regulations, catalyst bed bypassing had to be completely avoided. To facilitate this, Anguil altered their traditional design and placed the base metal catalyst in horizontal tray configurations. This minimized the bypassing concerns associated with air passing around the catalyst media or bed.

To keep operating costs down and prevent leakage that could result in a comingling of the clean and dirty air streams, a 65% effective 304L stainless steel leak-and-dye tested shell and tube heat exchanger was used in the oxidizer. Unlike other manufacturers who recommended a plate type heat exchanger, Anguil was able to guarantee 0% leakage of VOC-laden air into the clean air stream. As a fail-safe, Anguil installed an induced draft fan on the catalytic oxidation system. By placing the fan on the discharge side of the oxidizer rather than placing it on the inlet side, the system was under a continuous negative pressure. This meant that any leakage associated with the oxidation system would be released back into the system, rather than out into the work environment.

The entire interior reactor of the oxidizer was constructed of 304L stainless steel, surrounded by mineral wool insulation and an outer aluminized steel frame. This unique design offers multiple benefits, including increased equipment life compared to the industry-standard aluminized steel reactor interior. Another accommodation Anguil had to consider was the customer’s time restrictions due to high production levels. Anguil’s solution was to completely pre-assemble, pre-wire and pre-test the system prior to shipment. The customer’s 18-hour time restriction was met with time to spare.

Controlling Pharmaceutical Coating & Drying Process Emissions

Comments Off on Controlling Pharmaceutical Coating & Drying Process Emissions The Challenge

The Challenge

Originally published in Tablets & Capsules Magazine

Capturing and destroying harmful emissions from pharmaceutical processes can be challenging. It’s not because the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are difficult to destroy using catalytic or thermal techniques. It’s because their concentrations can be so high. These process streams raise safety concerns, both when they’re collected in vents and when they reach the final combustion equipment. This article discusses the options.

Catalytic and thermal oxidation are the two best technologies for destroying VOCs in emissions from pharmaceutical and other operations. Both use high-temperature combustion to break down pollutants, leaving only carbon dioxide (CO2), heat, and water vapor. Pharmaceutical operations, however, typically require customized emission control systems to handle the high VOC concentrations that emanate from tablet coating, fluid-bed processing, and tray drying. Often the concentrations reach the explosive range, which means the emissions must be diluted before they’re introduced to an oxidizer to ensure a safe operation that protects employees and property.

The Solution

Process background

Today, most tablet coatings are aqueous, but many pharmaceutical manufacturing operations still use VOCs such as ethanol and isopropyl alcohol (IPA). This includes the manufacture of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) that are dissolved in VOCs and then spray-dried to create an amorphous solid or granules. Most of these processes are batch operations, and that leads to significant and nonlinear VOC concentrations in their exhaust. In fact, the VOC concentration often exceeds the lower explosive limit (LEL) by 100 percent. In the presence of an ignition source and sufficient oxygen, these process exhausts—if not mitigated—will lead to an explosion.

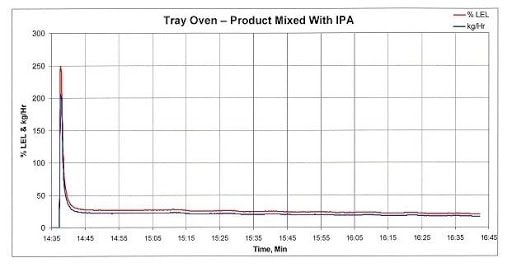

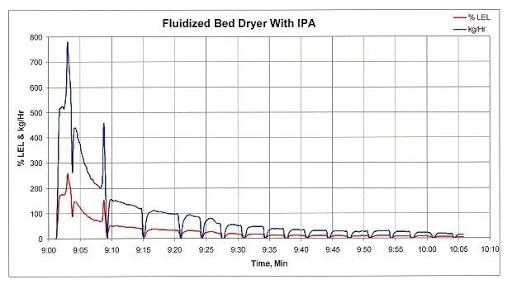

Figure 1 below tracks the emissions and LEL concentration of the exhaust from a fully loaded tray dryer that was measured after heat was applied to drive off the VOCs. Approximately 30 seconds after heat was applied, the IPA concentration peaked at approximately 250 percent of LEL. If this stream was delivered straight to an oxidizer operating at high temperature, there would be an explosion. About 8 minutes after spiking, the VOC concentration decreased to approximately 25 percent of LEL, which is the acceptance limit of most standard equipment that treat VOCs using catalytic or thermal oxidation.

Fluid-bed processors can generate the same peaks, as Figure 2 shows. In this case, the processor’s inlet air temperature is 40°C for 20 minutes and then remains at 45°C until the end of the production run. Following the initial product transfer into the fluid-bed dryer, the exhaust concentration reached an initial peak concentration of approximately 370 percent of LEL. Approximately 6 minutes later, a second VOC spike occurred after the process bowl was scraped. This second spike resulted in a peak concentration of about 200 percent of LEL. These exhaust concentrations, with an ignition source and sufficient oxygen, would result in an explosion.

Vent collection and oxidizer control software

In short, the data tell us that you should expect high VOC concentrations in emissions from coating, fluid-bed, and tray drying operations. There are two common ways to manage the peaks, mitigate the risks, and operate safely. The first is vent control software that recognizes when processes or batches are ready to start. It then “reserves space” for them in the vent collection system. The second method uses software in the oxidizer’s control system to identify how many processes are running. It then allows only one new process to come online to the oxidizer and only during a specific period.

The vent collection software puts you in communication with operators or links to automatic controls at each stage of production, signaling when it’s safe to come online and when to wait. If multiple demands to vent arrive at the same time, the software delays new batches and processing until it learns that exhausts from earlier batches are well beyond peak VOC concentration.

This control method uses the dilution capacity of existing process exhaust points—beyond their peak concentrations—to verify safe status and allow a new batch. If no processes are online to the oxidizer and a batch start is requested, then the software must verify that enough fresh dilution air is available. This software can also verify that sufficient fresh air is available to process several batches in quick succession, maximizing production.

The oxidizer control software works in the system’s PLC-based controls to communicate with operators or equipment to signal when more processes can come online. It could require, for example, a minimum number of processes to be online to the oxidizer for a certain period. That would indicate that the VOC concentrations are beyond the peak and a new source can come online. The software can also verify that a minimum amount of fresh air is sent to a new production source to dilute the exhaust before it reaches the oxidizer.

Even with this software installed, additional safety provisions for emission control would likely be incorporated following a plant-wide process hazard analysis (PHA). They would likely include LEL high-limit switches to prevent a dangerous concentration from entering the oxidizer or abatement device. Ideally, these LEL devices would be self-calibrating to minimize expenses and respond very quickly. A PHA would also show where to install LEL controls in relation to the process-exhaust and oxidizer-isolation dampers. Often, flame or detonation arrestors are placed in each process-exhaust line to mitigate damage to the processes if all other safety measures fail.

Emission control methods

Emission control methods

Catalytic oxidation

VOC emissions from many pharmaceutical coating and drying processes have historically been controlled with catalytic oxidation. The process is similar to how automotive catalytic converters treat exhaust. Process emissions pass through a catalyst that allows lower oxidation temperature to destroy the VOCs. Because the process emissions—often alcohols and/or acetone—are very catalyst-friendly, catalytic oxidation can remove VOCs at high rates. However, in contrast to automobile exhaust, these industrial emissions are at a low temperature and must be heated to activate the catalyst so it can oxidize the VOCs. Typically, this is done using the oxidizers gas-fired burner, often in conjunction with integral heat recovery to reduce fuel consumption. Recovering this thermal energy—typically at rates of 65 to 70 percent—also reduces the amount of CO2 emitted into the atmosphere because the system is more energy efficient and depends less on auxiliary fuel-fired burners.

The photo below shows an integrated catalytic oxidation system that incorporates the catalyst, integral heat exchanger, gas-fired auxiliary heat system, system fan, and a PLC-based control panel. This equipment controls the emissions from 12 pharmaceutical coating pans and tray dryers, as well as VOCs from an air stripper’s exhaust.

Although catalytic oxidizers have been used successfully in the pharmaceutical industry for many years, other control technologies have gained appeal because they can treat larger exhaust volumes more efficiently. Abatement equipment is also being used to control VOCs from more sources, which increases emission volume and the need to dilute emissions to safe LEL levels. The abatement equipment thus grows in size. In order to reduce costs, companies are opting for fewer but larger abatement devices.

Regenerative thermal oxidation

Like other industries where abatement equipment volumes have increased over time, the pharmaceutical industry is witnessing a shift from catalytic oxidation to regenerative thermal oxidation (RTO). RTO uses high-temperature combustion (with little supplemental fuel) to break down pollutants, converting them into small amounts of CO2, heat, and water vapor. Specifically, the process gas and contaminants are progressively heated as they move through insulated chambers filled with ceramic media. Once oxidized in the combustion chamber, the hot, purified air releases thermal energy as it passes through a second media bed in the outlet flow direction. Valves alternate the airflow direction into the media beds to maximize energy recovery within the oxidizer. The outlet bed is heated and the gas is cooled so that its temperature at the outlet is only slightly higher than it is at the process inlet. This greatly reduces the need for auxiliary fuel, which lowers operating costs.

RTOs can also provide very high VOC oxidation efficiency but do so at higher combustion chamber temperature without the need for catalyst to maintain that temperature. Even at RTO’s higher operating temperatures, auxiliary fuel usage can be lower compared with catalytic oxidation because RTOs energy recovery and thermal efficiency are generally 95 percent but can reach values as high as 97 percent. Thus, auxiliary fuel consumption and the resulting CO2 emissions to atmosphere are lower with an RTO device than they are with a catalytic oxidizer.

Larger air volumes also argue in favor of RTO devices because they are generally built of carbon steel. That reduces their cost compared to catalytic oxidizers, which not only incorporate precious metal catalysts, but are also primarily built of stainless steel. (RTO devices that handle halogenated VOCs are built using higher-cost alloys to resist acidic gases.) While RTO devices are replacing catalytic oxidizers in many cases, the selection depends on the application. One drawback of RTO is that the equipment is much heavier, which reduces installation options.

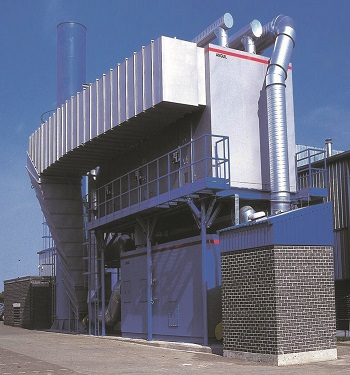

The photo below shows an RTO system Installed at a pharmaceutical plant. It controls emissions from four tray dryers, 13 fluid-bed dryers, and three coating pans. Much like the catalytic oxidizer shown above, the system incorporates LEL controls to verify a safe operating system. Because it’s located in a cold-weather area, any dilution air that’s added is heated to minimize the chance that water or VOCs will condense within the abatement system.

When processes emit extremely high VOC concentrations and exhaust flows are very large, dilution becomes more difficult, and the abatement system can grow quite large and expensive. In those cases, emissions that are soluble in water, such as alcohols, can be treated using a wet scrubber. The VOCs, however, will likely be transferred to a water stream for disposal, which may be an additional burden on the facility. In addition, the vapor pressure of the alcohols can be relatively high, which means that the wet scrubbers often use “once-through” water. That raises concerns about the volume of water used and how to dispose of it. Even so, this method has been used on occasion to control high concentrations of VOC (alcohol) emissions. In some instances, wet scrubbers are used in conjunction with oxidation equipment such as RTOs.

The Result

When designing abatement systems for pharmaceutical processes that involve coaters or dryers, understand the emission types, what the VOC concentrations are, and how they fluctuate during processing. Next, conduct a PHA to identify the design requirements for the abatement system to operate safely and effectively.

Once you have determined the flow and total VOC emission rate from the facility, consider all the technology options for removing the VOCs. Catalytic oxidation remains a viable technology for relatively small exhaust flow rates. RTO offers lower capital and operating costs at process exhaust flows of 5,000 SCFM (8,025 Nm3/hr) or larger. Wet scrubbers also warrant consideration, even though their high consumption of water and the need to dispose of the wastewater make it unattractive in many applications.

Reactor Vent Emission Control

Comments Off on Reactor Vent Emission Control The Challenge

The Challenge

Many chemical and petroleum companies use batch reactors to make their products. These reactors typically have vents which are opened and closed during emptying, filling, mixing, heating or cooling and other steps of the production process. The gases coming from these vents must be controlled under most government regulations. Often the emissions produced are inert (little or no oxygen) streams with relatively low flow and high concentration of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). In this case, the company was operating several reactors that required venting for depressurizing, filling and mixing. The process flow rate was less than 50 SCFM (80.25 Nm3/hr) and was essentially all light hydrocarbons such as methane, ethane and propane, with some halogenated hydrocarbons.

There are two oxidation strategies for this type of process stream, the first is to dilute the process vent with fresh air. This strategy provides oxygen for combustion and reduces the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) below 50%, using a conventional oxidizer system. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) and FM Global guidelines suggest facilities keep vent collection systems airstreams below the 50% LEL for safety reasons. Because of the high BTU (British Thermal Unit) content of the process vent in this application, it would have required a high volume of fresh air to achieve the necessary LEL condition which would have dramatically increased operating expenses and raised safety concerns.

The Solution

The Solution

While the above scheme is sometimes acceptable, Anguil implemented a different, safer strategy for this application. Instead of diluting the process vent with fresh air, designers kept the process stream inert, sending it directly through a burner port of a Direct Fired Thermal Oxidizer (DFTO). Essentially this allowed the combustion device to use the high BTU content as fuel for oxidation.

Once the DFTO is brought up to operating temperature with natural gas, the inert process gases are directed to the burner. During normal system operation, the VOC-laden process vent will fuel the pollution control device. During periods of low process flow or low energy content, supplemental fuel is added to the burner, natural gas in this case, to maintain operating temperature of 1400-1600°F (760°C-870°C) in the oxidizer combustion chamber. A minimum of one second residence time at these temperatures ensures a destruction efficiency of 99%+. An oxygen meter in the exhaust stack ensures that sufficient oxygen was present for complete destruction of the VOCs.

A soft refractory lining inside the oxidizer lets the operator start and stop the system without risk of refractory failure that can occur with other designs. This also allows them to shut down the oxidizer during substantial periods of process downtime without negatively affecting the longevity of the equipment.

For inert gases that contain no halogens or sulfur compounds the hot, purified, gas will be released to atmosphere from the combustion chamber or possibly sent to a heat exchanger for energy recovery. This particular application contained halogenated compounds, therefore the hot exhaust gases leaving the DFTO are directed into a hastelloy quench where they are cooled down before entering a packed bed scrubber.

The recirculation with a caustic solution inside the scrubber removes HCl (Hydrochloric Acid) and HBr (Hydrobromic acid). The scrubbed gases are then pulled into an Induced Draft fan and finally out an exhaust stack. An induced draft fan is used with halogenated streams so that there is no potential for corrosive gases escaping to atmosphere. Any leakage of acid gases will result in substantial risk to equipment longevity and to personnel. These scrubbing systems provide 99%+ removal of the acid gases prior to discharge to the atmosphere.

With these acid gases there is also a potential for corrosion of the oxidizer shell behind the insulation if the metal temperature is below the acid dew point. To prevent that from occurring, the oxidizer is designed with an external shroud to keep the carbon steel shell at a temperature above the acid gas dew point, avoiding corrosion concerns.

The Result

The Anguil System has a complete control system with communication capability to DCS (Distributed Control Systems) systems and modems for remote monitoring / diagnostics. These controls provide for automatic purge, system heat-up and a wide range of operating conditions. Magnetic driven scrubber recirculation pumps and scrubber controls are also provided for automatic operation without personnel adjustments.

Plastic Components Painting

Comments Off on Plastic Components PaintingThe Challenge

A plastic injection molding company in Wisconsin is known as a world-class leader in the industry for their secondary decorating and assembly capabilities. One of their eleven facilities not only perform plastic injection molding but also provides the organization with decorating capabilities such as painting, laser etching, laser marking, pad printing and assembly of automotive, telecommunication and consumer products.

Over the years and through the 1990’s the operation ran successfully with a minor source air pollution control operation permit. This permit consists of very specific requirements to meet the Environmental Protection Agencies (EPA) LACT (Latest Available Control Technology) regulation. These included restricted limits on volatile organic compounds (VOC) per gallon of paint, catalyst, thinner and cleaning solvent as purchased. This limited the types of paints and colors they could offer customers but given the customer needs and production volume at the time, this was a manageable situation.

As the business grew, requests by customers for more exotic forms of paint and colors increased and they realized the need to increase their paint capabilities to compete. In December 2000 they applied for two new permits with The Department of Natural Resources (DNR), one for an air pollution construction permit to install a new state of the art robotic paint line system and the other for the ability to paint small metal parts. This permit modification changed the facility from a minor source of less than 100 tons per year of volatile organic compound emissions to a major source with the potential to emit over 225 total tons.

With the new permit, they not only had to meet the LACT requirements for the painting of plastic parts but now also needed to meet the MACT (Maximum Achievable Control Technology) requirements for the painting of small metal parts. The MACT requirements added a higher level of restrictions to VOC’s per gallon of paint as applied to metal parts. These restrictions were applicable and once again manageable.

Although the new permit allowed them to meet additional painting volume capacity requirements, they observed continued demand by their customers for paints that could not be used under the air permit. Additionally, with the acceptance into the ISO 14001:1996 standards, they realized the need to significantly reduce their VOC emissions.

The Solution

The only way to meet the customer demands and reduce emissions was to evaluate various forms of pollution control technologies. Anguil’s group of engineering experts convened to explore the various control technologies currently available on the market. Consideration was given to equipment/concepts such as:

- Catalytic Oxidizers

- Thermal Oxidizers

- Regenerative Thermal/Catalytic Oxidizers

- Emissions Concentrator Coupled with a Regenerative Thermal Oxidizer

- Microwave VOC Reduction Technologies

- Biofilter VOC Reduction Technologies

The company began to work very closely with the sales and engineering team at Anguil and the DNR to establish the best available control technologies to meet the pollution control requirements. With some simple calculations, Anguil was able to show how a Regenerative Thermal Oxidizer (RTO) would be the most cost-effective control technology for their current and future process demands.

The Result

After thoroughly evaluating several suppliers the company decided to go back to the Department of Natural Resources and request a new air pollution control construction permit to install a Anguil Model 400 / 40,000 SCFM (62,800 NM3/hr) Regenerative Thermal Oxidizer (RTO) for their existing paint operations.

The oxidizer would achieve destruction through the process of high temperature thermal oxidation, converting the VOCs to carbon dioxide and water vapor while reusing released thermal energy to reduce operating costs. Process gases with VOC contaminants enter the oxidizer through an inlet manifold. Dual disk poppet valves direct this gas into energy recovery chambers where the process gas is progressively preheated by the ceramic media beds as they move toward the combustion chamber.

The VOCs are oxidized in the combustion chamber, releasing thermal energy in the structured ceramic media beds that are in the outlet flow direction from the combustion chamber. These outlet beds are heated, and the gas is cooled so that the outlet gas temperature is only slightly higher than the process inlet temperature. Fast acting vertical poppet valves alternate the airflow direction into the ceramic beds to maximize energy recovery within the oxidizer. The VOC oxidation and high energy recovery within these oxidizers reduces the auxiliary fuel requirement and saves operating cost. For example, at 95% thermal energy recovery, the outlet temperature may be only 70`F (40`C) higher than the inlet process gas temperature with an RTO. The oxidizer can reach self-sustaining operation with no auxiliary fuel usage at low VOC concentrations.

Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) control the automatic operation of the oxidizer from startup to shut down, so minimal operator interface is required. These controls also provide for remote telemetry to enable the system’s operation to be viewed and altered via remote connections to reduce maintenance costs.

Later that fall the permit was accepted by the DNR for an air pollution control construction permit to install an Anguil Regenerative Thermal Oxidizer. Anguil Environmental Systems was able to complete the design, fabrication, delivery, installation and startup of the RTO so it could go on line early the next year.

After startup of the new RTO, a stack test measured 99% destruction rate efficiency for volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions at 100% capture. This equated to a net reduction of 58 tons of VOC emissions in the first 6 months of operation.

The benefits of installing the RTO included the ability to offer customers a large variety of paints and colors to meet their more unique paint finish requests. Also, the RTO allowed the manufacturer to use previously restricted thinners and paints to better process their products with fewer rejects. This allowed the business to grow and succeed in an increasingly competitive environment and meet the new demands from customers while significantly reducing the amount of volatile organic compounds released into the environment.

Paint Booth Over Spray

Comments Off on Paint Booth Over Spray The Challenge

The Challenge

A major automotive component supplier needed to control the emissions from its paint spray process. The plant emissions had characteristics common to many paint spray plants: high air flow, low volatile organic compound (VOC) concentration and particulate. The company needed an emission control solution that had low operating costs and that could also fit in their limited space. System reliability was also a major design consideration; since the company is a synchronized delivery partner to the automobile industry, plant downtime or process delays result in expensive fines.

The Solution

After an extensive technical evaluation of the proposed technologies and equipment manufacturers, the customer chose Anguil Environmental Systems to provide a turnkey solution for the VOC and particulate emissions. Anguil recommended an Emissions Concentrator coupled with a Thermal Oxidizer System to effectively process the 120,000 SCFM (190,000 Nm3/hr) of plant exhaust.

The Result

The cost of an emission control system is predominantly based on the volume flow rate of air that needs to be treated. Emissions from paint spray applications have historically been expensive to control because the process requires large volumes of air to maintain the quality of the painted products and to ensure acceptable indoor air quality. Anguil’s Emissions Concentrator technology makes VOC emission control cost-effective because it greatly reduces the air volume that needs to be processed by the oxidizer.

In this case, the Emissions Concentrator reduces the flow rate of process air that needs to be treated by a factor of 15, a major consideration in the capital cost of the system. The high-volume airstream from the water wash paint booths and the curing ovens is passed through the rotor concentrator wheel, where the VOCs are adsorbed in the emissions concentrator rotor, purifying the high-volume airstream. This high-volume air is then exhausted to atmosphere. The concentrator wheel rotates continuously, transporting adsorbed VOCs into a desorption section where they are desorbed into a low volume heated airstream. After being desorbed from the wheel, the air volume has been reduced from 120,000 SCFM (190,000 Nm3/hr) to about 8,000 SCFM (12,700 Nm3/hr) and the VOC concentration of the air stream is increased to about 4,500 ppmv. This low volume, high VOC-laden air is then processed by the oxidizer. By isolating and treating only the contaminated air, Anguil can provide a system with operating costs far lower than alternative emission control systems.

Innovative technologies like the Emissions Concentrator are just part of the solution Anguil provides. Anguil believes a complete solution involves careful analysis of the emission-producing process and engineering that is focused on the customer’s specific application. As always, Anguil worked closely with this customer to identify and solve their key concerns.

System reliability was the first concern for this customer. The plant is a Tier One supplier to the automotive industry and must meet very stringent delivery deadline requirements. Failure to meet a delivery schedule can result in fines of up to $30,000 a minute. One of the reasons Anguil recommended the Emissions Concentrator system is its highly reliable performance. Anguil took extra steps to integrate the system into the existing process and engineered the system with safety controls and advanced Programmable Logic Controls (PLC) for trouble-free operation.

The next design consideration was the tight space restriction. Due to several plant expansions, the facility had reached its legal minimum of parking spaces and nearby residential development meant the company could not purchase additional land. Local zoning restrictions also required the planned equipment to meet strict noise limits. Therefore, the emission control system had to be designed with the smallest possible footprint and with low noise generation. Anguil’s customer-specific engineering accommodated the unique space restrictions with a major advance in Emissions Concentrator/Oxidizer system design. A vertical arrangement that greatly reduces the unit’s space requirements gave the system a footprint that is 70% smaller than the space requirements for the Regenerative Thermal Oxidizer (RTO) proposed by several competitors. Additionally, the design incorporated several sound attenuation features to satisfy the low-level noise requirements.

Another major concern was controlling the high level of particulate in the paint spray exhaust. Particulate control was necessary to protect the concentrator rotor and to satisfy the low particulate emission limit. Anguil supplied a highly efficient filtration system designed for simple, low-cost filter replacements that can be easily changed out during scheduled maintenance.

Anguil’s solution included a complete on-time turnkey installation. The system was seamlessly integrated into the existing process and is exceeding regulatory requirements. Anguil’s combination of proven application-specific engineering and technologically advanced products has led to yet another satisfied customer.

Paint Mixing

Comments Off on Paint Mixing The Challenge

The Challenge

A company involved in the automotive aftermarket had a paint batch mixing and filling operation that used primers and fillers. They were faced with installing air pollution control equipment to handle the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by the solvents used in their processes. An independent consultant had determined that total exhaust volume from the facility was 28,000 SCFM (44,940 Nm3/hr) of air and as is often the case with painting operations this air contained relatively low concentrations of solvent vapors. This combination of high exhaust volume and low vapor concentration posed an operating cost problem. In addition, powdered material dumped into the batch mixers generated dust, causing potential OSHA violations and hazards to the operators.

The Solution

After thorough technical evaluation, Anguil Environmental Systems, Inc. was selected and contracted to solve the VOC problem and satisfy EPA requirements.

Anguil analyzed the operation and focused on the composition of the solvents and the high air volume. Of the solvents used, a small portion was methylene chloride. Chlorinated compounds are a potential poison to most catalytic systems and the company’s consultant recommended a thermal incinerator. Anguil recognized that a less expensive alternative to a thermal unit would be an Anguil Chloro-Cat capable of processing the chlorinated compounds. However, Anguil recommended evaluation of alternate compounds to replace the chlorinated organics. Upon investigation, the company chemist determined that all the chlorinated compounds could be replaced with regular organic solvents.

The high air volume was then addressed. One of Anguil’s strengths is our knowledge in capture hooding and air flow reduction techniques. The 28,000 SCFM (44,159 Nm3/hr) of exhaust was originally recommended based on the assumption that all thirteen (13) batch mixing devices could potentially be at their peak mixing and vapor loading capacity simultaneously. Interviewing the facility manager, it was determined that not all thirteen mixers were ever loaded simultaneously.

With this information, Anguil developed and designed an air reduction system after mapping the fugitive VOC’s with a portable FID (Flame Ionizing Detector). This research allowed engineers to determine the areas of high VOC concentration and subsequently design the innovative capture system that drastically reduced the amount of treated air.

The Result

The company had been using floor sweeps as part of their capture system that were up to ten (10) feet away from the mixing devices. The mixing containers had covers that were poor fitting and extremely heavy. The distance between the floor sweeps and the mixing devices was the primary cause of floating dust and escaping vapors. The solution included replacing the floor sweeps and mixing tank covers with a close capture hooding system. Anguil designed a series of aluminum custom fabricated mixing covers with integral flexible duct connectors to draw the vapors and dust directly from the mixers. The added benefit of the close capture hooding was the decrease in air volume necessary to capture the vapors from the VOC source.

Anguil determined that all of the VOC’s from the mixing room could be adequately captured with 9,000 SCFM (14,194 Nm3/hr) of air and that future plans for expansion would not take the exhaust air volume above 12,000 SCFM (18,925 Nm3/hr). Rather than focusing on costly outside make-up air to replace this 9,000 SCFM (14,194 Nm3/hr) of exhaust, Anguil supplied close capture pick-up hoods in the mixing room immediately adjacent to the room containing the fill devices. This air was then transferred or “cascaded” into the adjacent mixing room, creating makeup air. The VOC concentration of this makeup air was well below the Threshold Limit Values (TLVs) but the state regulatory authorities determined that these VOC’s were fugitives and should be destroyed. The air supply was introduced on the far side of the mixing room which helped sweep the vapors across the 120 by 60-foot room towards the pick-up points.

Outside of the building, an Anguil 12,000 SCFM (19,260 Nm3/hr) catalytic oxidizer was supplied and installed on a concrete pad. Prior to entering the catalytic oxidizer, the entire airstream was fed through a two-chamber dust collector to prevent the particulate and dust from masking the catalyst or blocking the oxidizer’s plate type heat exchanger. A precious metal platinum catalyst was supplied to destroy the hexane and toluene organics. Adequate catalyst was supplied to process 9,000 SCFM (14,194 Nm3/hr) and as the facility capacity increased, more catalyst would be added. Due to the well-designed air reduction strategy, Anguil saved the customer tens of thousands of dollars on their pollution control system while achieving compliance.

Natural Gas Production

Comments Off on Natural Gas Production The Challenge

The Challenge

The largest U.S.-based independent oil and gas producer and one of the largest independent processors of natural gas and natural gas liquids in North America was in search of new technologies to maintain the pollution control efficiency at their natural gas treatment facility.

In typical gas plants, the wellhead natural gas needs to be treated to remove water, CO2, any sulfur compounds and heavy hydrocarbons before it is sent to the pipeline. The acid gases formed by CO2 and H2S are normally removed by amine adsorption. The amine must then be stripped of these acid gases in order to be reused. The amine stripper off gas (tail gas) needs to be treated before discharge to atmosphere to remove residual hydrocarbons and meet EPA regulations.

The Solution

Gas and oil plants have historically used direct-fired thermal oxidizers with no heat recovery for tail gas treatment. The existing thermal oxidizer at this facility was using a considerable amount of auxiliary fuel to maintain temperatures of 1,500°F, ensuring all the organics were combusted but costing them a significant amount of money in operating costs. Dedicated to finding a less expensive means of regulatory compliance, the oil and gas producer challenged several air pollution control manufacturers to provide a system that was not only effective, but also energy efficient.

When Anguil was approached to address the air pollution control needs at this facility, careful measures were taken to assure the proper equipment selection.

The Result

After much consideration, Anguil offered their Model 75 (7,500 SCFM, 12,037.5 Nm3/hr) Regenerative Thermal Oxidizer (RTO) with heat recovery for efficient and effective operation. Anguil was selected because of their unique approach toward air pollution control and energy conservation.

With the Anguil two-bed RTO, the contaminated process gas is pre-heated as it passes through beds of ceramic media located in the energy recovery chambers. The process gas moves from the pre-heat chamber toward the combustion chamber, where the Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) are oxidized, releasing energy into the second energy recovery chamber before going to atmosphere. A diverter valve switches the process gas direction so both energy recovery beds are fully utilized, thereby reducing any auxiliary fuel requirement. This system is designed for heat recovery of 85% and is self-sustaining, requiring little auxiliary fuel use. This energy-efficient design offers significantly lower operating costs in comparison to other emission treatment methods.

The RTO is designed to prevent corrosion by the acid gases and to handle the high organic loading with low oxygen levels. The gas at this facility is “sweet” and does not contain any H2S but precautions were taken to prevent carbonic acid attack due to the CO2. In addition, Anguil provided a Class 1, Division 2, Group D control package. Heated, fresh air was also introduced into the system, providing supplemental oxygen without condensing moisture in the process stream. Anguil’s application specific engineering was an important factor in the success of this project.

The Anguil RTO is achieving 99% DRE (Destruction Rate Efficiency) and is saving the customer more than $500,000 per year in natural gas costs. Anguil’s equipment, detailed system design, installation and startup has exceeded the customer’s expectations of efficiency and affordability.

The Challenge

The Challenge The RTO in Action

The RTO in Action The Challenge

The Challenge The Result

The Result The Challenge

The Challenge The Result

The Result The Challenge

The Challenge The Challenge

The Challenge

Emission control methods

Emission control methods The Challenge

The Challenge The Solution

The Solution

The Challenge

The Challenge The Challenge

The Challenge The Challenge

The Challenge